Befitting the land-grant university of a sprawling and diverse state, the hockey teams of Cornell University have made rinks resting along the banks of the Hudson nearly as homey as the Red's traditional home nestled in the breast of the Finger Lakes. Hockey teams of Cornell have squared off against opponents in contests in Manhattan for over a century. At least four venues have hosted Cornell hockey contests. Cornell has played in at least 36 games in the nation's largest city. The Big Red has emerged victorious in 19 and settled for a tie but once in all of those contests.

No Roof Over Its Head

Cornell's first foray into Downstate hockey ended disappointingly in a 5-0 loss. Each team injured a player of its challenger's squad. Cornell's Lewis, who was struck over the eye, did remain in the contest. Cornell played almost exclusively in its end during both halves.

The Big Red would not need to wait too long for redemption. The second and third contests that the Cornell icers played in New York City occurred in January 1903. St. Nicholas Rink generously hosted again. The star of Cornell's first win was forward Lewis. He was one of the injured parties in the previous year's contest. Armstrong and Preston joined a Cornell scoring rush that toppled Princeton, 4-0.

The uncoached Cornell squad proved unable to focus after an emotional win. The Big Red succumbed to the reigning national champion Bulldogs of Yale the next day.

It took the arrival of Cornell's second coach for the Big Red to establish dominance in Manhattan commensurate with its effervescing national dominance. Talbot Hunter led his charges in four contests at St. Nicholas Rink during the 1909-10 season. Princeton, Harvard, Yale, and Columbia were the opponents in order for those meetings.

The Princeton and Harvard contests were played with three days of separation. The Yale and Columbia contests occurred with the former coming a month after the Princeton game and the latter a month after the former. The path from idyllic Central New York to the bustling city was well trodden.

Cornell would win the back half of the series, sweeping Yale and Columbia by a combined margin of 10-2. It is the second loss that is remembered. In the first meeting of the archrivals, Cornell and Harvard played a slow-paced game that experienced no scoring in the first half. This gave way in the second half to a Crimson-tinted pummeling that embarrassed Cornell, 5-0. The centrality of the Cornell-Harvard rivalry to the history of Cornell hockey and New York City's hosting of the first contest between the archnemeses illustrate the impactful role that Cornell's games in Manhattan always have had on Cornell's hockey tradition.

The ninth hockey team to represent Cornell University was a team of destiny. This second squad of Talbot Hunter would record one of the Big Red's five perfect seasons in hockey. An all but inevitable national title laid at the end of its run. Predictably, St. Nicholas Rink, as the nation's premier skating venue in the early 20th Century, waited in anticipation for many of college hockey's greatest moments as Cornell began its season in the West.

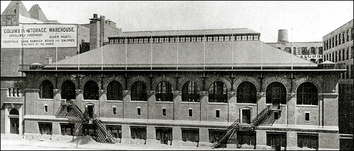

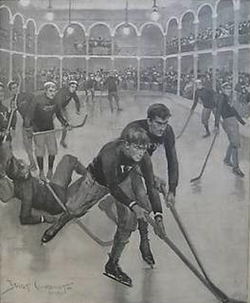

At 69 West 66th Street on the northeast corner of 66th Street and Columbus Avenue stood hockey's greatest venue for generations. It bore the name of St. Nicholas Rink. More suitably, it would have born the appellation "palace." Much like the Victoria Skating Rink in Montreal that birthed the game of hockey into existence, St. Nicholas Rink would leave modern observers with the impression of a grand dance or banquet hall.

Seating was limited. It was not in short demand. The venue became crowded regularly. The sprawling artificial ice surface conquered the greatest area of the arena. Deliberate and ornate pillars extended from the primitive boards that framed the ice to the soaring ceiling. Alternating between pillars, arches rose and descended to frame the game for spectators on the second tier. Those in attendance crowded along the railings that restrained them on the second story. Descending from the heavens of the venue were lamps to illuminate the heated contests below. The attire of most attendants was typically of the tie variety, black or white, that is. St. Nicholas Rink exhibited the grandiosity that one would have expected of a venue that John Jacob Astor and Cornelius Vanderbilt benefacted. As the pond represents hockey in its purest, untainted form, arenas like St. Nicholas Rink were its first great coliseums.

Greatness proportional to its setting was exactly what Cornell brought to St. Nicholas Rink during its 1910-11 season. Famed winger Jefferson Vincent scored one minute and 15 seconds into Cornell's first contest in Manhattan. Princeton knew that the team from New York's land-grant university would win the day. Cornell defeated Princeton, the defending national champion, by a 4-1 final margin. The crowd at St. Nicholas Rink was pleased.

Yale was the next victim to Cornell hockey's emergence as the home team in New York City. The game had drawn considerable interest from the alumni of both schools and large swaths of the Downstate public. "Great interest is being shown in tonight's game and a large attendance is predicted," boasted The Yale Daily News.

The Bulldogs of Connecticut fared one goal better than did the Tigers of New Jersey, but their fate was no more kind. Pucks leaving Vincent's stick were kept out of the Elis's net for an impressive three minutes. Crassweller scored from center ice. Magner scored on a one-man, length-of-the-ice breakaway. Vincent added a second tally. Vail drew applause with every save. The Big Red could do no wrong in Manhattan.

Even the natives of Morningside Heights found themselves out of sorts against Cornell at St. Nicholas Rink. Columbia departed for its short trip back to campus with a 4-0 loss to Talbot Hunter's 1910-11 squad. As Cornell was undefeated and widely supported everywhere else during the 1910-11 season, it was unsurprising that it would be undefeated and overwhelmingly supported at St. Nicholas Rink.

Cornell's margin of victory was one and a half times greater in Manhattan than it was when playing IHA opponents elsewhere. The Big Red posted its only shutout of an IHA opponent in the friendly confines of St. Nicholas Rink. Cornell had become New York.

Cornell's run of success in New York City suffered a slight downturn over the next several seasons. From the end of the 1910-11 season through that of the 1913-14 season, Cornell posted three losses at St. Nicholas Rink. The collapse of the IHA caused Cornell to cultivate contests with Upstate New York foes rather than seek contests within the City. This necessitated a seven-year absence between Cornell contests played in New York City. Cornell returned in 1921.

Nicky Bawlf, the longest tenured coach in Cornell hockey history, drilled his squad in anticipation of a return to New York City. The contest, unlike all those that Cornell played previously in Manhattan, was not played at St. Nicholas Rink. The match was held at Columbia University's home rink, the 181st Street Ice Palace. The reunion of the City and Cornell was a spectacle.

Reflecting drastic changes in the game over a mere seven years, hockey now was played in three periods rather than two halves. The essence was immutable. Whether one played it on a natural pond or an artificial ice surface, it remained Cornell's impassioned pastime.

Columbia and Cornell were tied after two periods. Both New York-based teams had solved the opposing netminder twice. Columbia leapt to an early third-period lead. Cornell responded. As if anticipating that this would be Cornell's last contest in New York City for a generation, the Red ignited for four rapid tallies to gain the lead and expand its margin to three goals. The deluge of Ithacan goals came with but a few minutes remaining in the contest. Finn and Thornton led Cornell as its decimated Columbia, proving to the team and fans alike that while Columbia might be hosted in New York City, the City's great love was Cornell.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed