It may surprise most that the evening discussed above is not the moment when NCAA Division I hockey began its slog to Pennsylvania's land-grant university. It is likely the most essential moment in the decades-long battle to establish college hockey's marquee level at Penn State. It is not the germ that precipitated the brand of Penn State Icers hockey that laid latent until Nittany Lion hockey allowed the coinage of "Hockey Valley."

Dormant would have been Penn State's chances at establishing NCAA Division I hockey if the events of another evening had not taken place. It was a snow-swept evening in the frigid environs of a pastoral countryside. A translucent gloss overcomes a driver's windshield as he tries to outwit the snowfall to see but a glance of what lies before him on the roadway. A flick of his wrist turns on his blinker as he sees a tall silhouette along the roadside. The driver brings his car to rest along the side of the roadway. He motions to the would-be hitchhiker that he can approach and enter the car. The big kid approaches the car. He opens the door, but turns the page miles and years distant.

This moment was not in Central Pennsylvania. It was nearly 200 miles north in Central New York.

Similar but Unalike

Pennsylvania's meddling in its laboratory of democracy instilled hope in legislators like Morrill and civic-minded industrialists. The land-grant model was viable. With no members of the Southern delegation to oppose it and a favorable president in Abraham Lincoln, the Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1862 for the sale of federal lands passed. Cornell University would be founded as a result in 1865, 10 years after the Pennsylvania State University was.

The visionaries of Cornell University represented the dualism expected of a great land-grant university. Ezra Cornell sprang from the salt of the Earth and was a self-made industrialist. Andrew Dickson White was a rigorous and respected academic, but he was of a privileged birth. They were the unconventional and conventional. They incorporated the social mobility of the American ethos and traditionalism of the great university. The two are what made Cornell University an equal-opportunity meritocratic institution that dared to teach and mine fields long neglected or disparaged while adhering in its liberal arts education to the rigor of the Old World.

The Pennsylvania State University needed to find these balances, but in only one man. Evan Pugh was the founding president of Penn State. He had the unenviable need to serve as his University's Cornell and White. He would manage. Pugh, like White, was educated in the burgeoning tradition of great German research institutions.

Pugh attended the University of Gottingen while White attended Frederick William University. Like Cornell, Pugh had an appreciation for agriculture after his time at Great Britain's ground-breaking Rothamstead experimental plots. Pugh's vision of combining traditional rigor in areas of classical and modern study foreshadowed the philosophies that Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White would venture to perfect. Pugh died not long into his presidency.

The reciprocity and diffusion between New York's and Pennsylvania's land-grant universities did not halt. The New York Legislature, whose inhabitants were early antagonists to the creation and ambitions of Cornell University, bore down on Ezra Cornell. A distrustful eye was cast at his choice of land holdings in Wisconsin. The legislative body accused the great philanthropist and industrialist of illegal and unethical land speculation. It alleged that his conduct and the entire land-grant experiment by extension was corrupt. Ezra Cornell faced these accusations in Albany to defend his greatest endeavor. He would do so before his death. He had an ally who would come to shape the history of the Pennsylvania State University and all land-grant universities.

George Atherton was a professor at Rutgers University. A Yalie like Andrew Dickson White, he came to use the academy to advance civic service after his serving in the War Between the States. His academic focus was an empirical study of the historical and sociological effects of the Morrill Land-Grant Act. His first formal report came months before Ezra Cornell died. Atherton refuted the claims of corruption and usury against land-grant institutions, including those against Cornell University. It was the poignancy of his arguments that arrested a half-generation-long assault on institutions like Cornell and Penn State. He secured the future of land-grant universities.

The Pennsylvania State University appointed George Atherton as its seventh president. As a student of the land-grant model, he was keenly aware of the approaches that Cornell University had adopted to integrate traditional and practical education. Atherton became the first president at Penn State to manage to feed the mind of the traditional academic while teaching those in his state to hone the skills to feed a growing nation. Cornell's example informed his balance.

Atherton and White were the leaders who saw that their institutions could achieve two objectives that had been regarded as incompatible for generations. They so inspired their students in their 19th-Century makeshift university classrooms that similar stories recount both institutions early days. Students at Penn State took to teaching themselves Classics when the institution neglected liberal arts education in its early era. Their stated objective was to surpass the reputations of Harvard and Yale. Students at Cornell were far less modest. In what is regarded in campus lore as the first question on Cornell's campus, British explant Goldwin Smith fielded a question from a student. The pupil from Cornell University's first class asked, "how long would it take for the reputation of Cornell University to surpass that of Oxford?"

Bearing similar ambitions, the two institutions diverged in one key regard. The first collegiate football game was played in 1869. Cornell students embraced the sport quickly. In 1874, the University of Michigan invited Cornell's team to play a contest in Cleveland, OH. Andrew Dickson White infamously dismissed the invitation with the words "I refuse to let 40 of our boys travel 400 miles merely to agitate a pig’s bladder full of wind!” White saw little utility in nascent collegiate athletics.

George Atherton would act much differently eight years later at Penn State. Atherton saw in college football a catalyst to unify a campus that had little self-pride. He had brought football and given it a home in just over a decade as president of the University. Beaver Field was completed three years before the first collegiate hockey game.

Andrew Dickson White's suspicions of large-scale football lingered with Cornell. They presaged the Ivy League's eventual self-imposed postseason football ban. Cornell would become influential and prominent in football. It was Cornell that gave the sport Glenn "Pop" Warner and claimed five national titles. However, the Big Red's refusal to accept an invitation to the 1939 Rose Bowl manifested deep-seated suspicions of the sport that attached after White's comment in 1874.

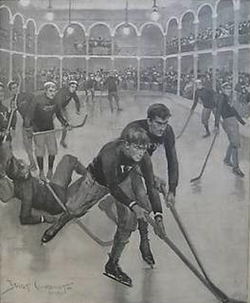

College hockey was born in 1896. The sport would make its way to the frozen waters of Beebe Lake within four years's time. Andrew Dickson White had been absent from East Hill for a decade and half. The students of Cornell University needed a sport untainted by one of its founder's opinions that could unify them. Hockey became that sport.

Near Misses and a Collision

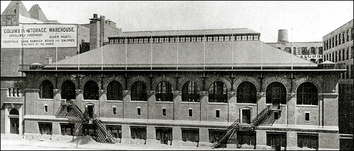

The 1909-10 season was a transformative one in the history of Cornell hockey. It was the season in which Cornell hired Talbot Hunter, the first coach to win a hockey championship for New York's land-grant university. Cornell began that season at Elysium Arena in Cleveland, OH. It was an inflection point for the program.

Separated by the time of one week and 135 miles to the southeast, Penn State began a similar journey on the evening of December 25, 1909. Penn State's first known organized hockey team was an invited member of an upstart league that rivaled the centralized and predominant Intercollegiate Hockey Association. The newly minted Pittsburgh Intercollegiate League was based out of Duquesne Gardens, where its first contests took place.

The Nittany Lions were greeted with tremendous support in Pittsburgh that season not unlike that which welcomed the Big Red to Chicago and Cleveland. Alumni and students supported their hockey program. Penn State dropped both of its contests in December 1909. Interestingly, an early eye cast toward Ithaca emerges in the coverage of the era.

The State Collegian reported that the "college game has made rapid strides in the last few years. Yale, Princeton, Cornell, Penn, Harvard, West Point, Dartmouth, Williams, Amherst, Tech, Pitt, and many other college have placed it on their athletic lists." Penn State knew that it wanted to be among those prestigious Eastern institutions. Hockey was an easy means of achieving that end.

The students of Penn State defended the continuance of hockey on these grounds. Editorials were written and opinions made known. They were to no avail. A vote of the Athletic Association of Penn State on January 21, 1910 defunded and denied Penn State hockey any further support from athletics at the institution.

Cornell and Penn State may have been separated by mere miles and days in their early collegiate hockey competitions, but their respective commitments to hockey could not have been further apart. While the latter dismantled a hopeful and youthful program, Cornell prepared for the winningest undefeated, untied season in college hockey yet. A perfect 10-0-0 season was a resounding success.

The Central Pennsylvanians noticed the rise of the Ithacans. On December 7, 1911, on the even of what could have been Penn State's third hockey season and what was Cornell hockey's ninth season, The Penn State Collegian ran a story aptly labeled "a plea for hockey." It captured the volksgeist of the student body. What was implied in late 1909 and early 1910 was demanded outright in 1911. "Penn State in a few years, will undoubtedly takes it place among the big universities," it anticipated.

The article, relying on the parlance of the era, conceived of "big schools" as Harvard, Yale, and Princeton, the colonial institutions with commitments to athletics. Drawing from Cornell's example, Penn Staters concluded, "there is a much greater chance of defeating [the big universities] in minor sports than in major." Administrative deaf ears were the audience for this impassioned plea. Penn State would need to wait another generation for collegiate hockey.

The first sustained era of Penn State hockey began in February 1938. A full season of 11 games was played for the 1939-40 season. The Nittany Lions would win three of them. The program would host only one confirmed home game in State College during its entire existence. The temperate weather of Central Pennsylvania was too much to maintain an ice surface and guarantee conditions that were safe and dependable for hockey contests.

Penn State, for similar but distinct reasons than those that plagued Cornell, had difficulties maintaining a home practice ice surface. From its early era onward, Cornell had attempted to drill and practice when needed. Odd games were canceled at Cornell, but Central New York in December through February is scarcely want of ice as was a problem in Central Pennsylvania. Penn State desired to experience it firsthand.

One of the earliest and certainly one of the most common programs to which Penn State reach out for contests was Cornell. The hockey players of the land-grant institution of Pennsylvania desired to square off with the Big Red of New York's land-grant institution. In the early days of the 1942-43 season, The Daily Collegian noted that Penn State sent requests for contests to two institutions: the United States Naval Academy and Cornell University.

The possibility of a series or even rivalry was not ignored in Ithaca. Three distinct reciprocated attempts were made. No games were played. The inclimate nature of outdoor rinks forced the cancellation of all of those contests from 1938 until 1944. The 1943-44 season changed all of that.

Cornell and Penn State, much like they did during the First World War, occupied different niches in American culture and higher education than did the traditional universities of the nation. As land-grant institutions, training in the military arts was an integrated part of their missions. The outbreak of the Second World War threw the students of each university into the same crucible that gave collegiate hockey the heroism and martyrdom of greats of the game like Jefferson Vincent of Cornell and Hobey Baker of Princeton during the First World War.

The first and only direct meeting between the hockey programs of Cornell and Penn State occurred in an epoch when the male students of each institution were expected to drill each morning to be prepared to be called into the military service of their nation. Reflective of this change in timbre, the historic Cornell Daily Sun adopted the name The Cornell Bulletin and received only weekly publication. It was under this masthead and cloud that Cornell met Penn State on Beebe Lake.

The contest was the third contest of Cornell's 36th season. The Big Red had lost by a combined margin of 12 to two in its first outings against Army and Colgate. This edition of Cornell hockey had high expectations that would go unfulfilled. Nicky Bawlf was unpleased with his team's first efforts. He expected to exact repentance before the Penn State contest. The Bawlfmen were drilled and skated on Beebe Lake until exhaustion before the Nittany Lions arrived.

As is typical of Cornell even at its low points, Ed Carmen, the netminder, was lauded for his exemplary play. Red netminders even in a seasons that began with 12 allowed goals were celebrated. The Bulletin bemoaned a lack of defense and blocked shots in the first game. Yes, blocked shots were already a thing of beauty to East-Hill occupants.

Penn State needed to rely on the good graces of nature to practice. Flooded tennis courts were where it drilled and practice. Beaver Field where football was played would have been a much better option. Harvard Stadium was used to host the Crimson hockey team during the winter months. However, the centrality of football to the identify of Penn State made such an option too risky to imperil the football pitch. The Nittany Lions practiced little.

The result may have seemed a forgone conclusion in retrospect, but Penn State hockey team earned the respect of its Cornell counterparts. Cornell was the faster and more dominant of the teams. Unlike the Red's efforts against Colgate and Army, Cornell gained sustained pressure. The throngs of bundled fans several deep along Beebe Lake witnessed as Penn State managed to compete in its own end.

The first period expired with Cornell registering one goal. The game resumed in the second period much the same way. Penn State held off Cornell with considerable poise. The Big Red found an answer to Penn State's netminder three times before the final period. The disparities in training condition and tradition began to emerge in the third.

Four goals were scored in the last 20 minutes. The icers of Penn State seemed fatigued. Cornell finally had worn them down. Penn State did exact some respect of the tangible not sentimental variety. The Nittany Lions did best respected Cornell netminder Carmen once during the contest. Cornell registered its first and what would be only win of the 1943-44 season, a 7-1 defeat of Penn State.

It is unclear whether respect of the institutional, athletic, or both varieties made the Cornell-Penn State dynamic different than most others in Cornell's post-IHA era. The game was described as "exceedingly tight until the last period when lack of conditioning of the Penn State skaters told." The land-grant universities of that era exhibited a collegiality that few institutions did.

Cornell attempted to return a trip to Central Pennsylvania for the 1944-45 season. The contest would be canceled. This phenomenon is remarkable nonetheless. Cornell was wiling to travel to a rink whose conditions were more suspect out of an abundance of respect. A few decades previous, it is easy to show how the land-grant identities of schools affected this nature.

The hockey program of Boston University was a rising national power in the 1920s. The hockey program of the University of Massachusetts, a fellow land-grant university, was prominent but not preeminent. It was against Massachusetts, not Boston University, that Cornell hockey scheduled and played home-and-home series in the Beebe Lake Era. Boston University was forced to visit Central New York with no expectation of a return trip.

This connection that the land-grant universities shared could not save Penn State. Just years prior to the creation of the NCAA tournament, Penn State's first era in varsity hockey ended. Similarly, yet unexpectedly, Cornell would cancel its program in 1948. Cornell's program would return in 1957. Penn State would need to wait for intervention of fate and the help of an unexpected person to bring hockey back to Centre County, PA.

That Evening

Ken Dryden was the name of the stranded pedestrian. As one may expect of an alumnus of History at Cornell University who most famous written work is The Game, the conversation veered toward hockey. The driver, Larry Hendry, indicated that he had never seen a game at Lynah Rink. Dryden insisted; he must see a game at Lynah.

See a game he did. Hendry was a doctoral candidate in the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology at Cornell University. As a graduate student, he had little initial exposure to the zeal that had become Lynah Rink during Cornell hockey's second dynastic era. It changed upon Dryden's urging. Hendry became immersed in the culture and traditions of Cornell hockey.

Larry Hendry was graduated from Cornell University with a PhD in 1970. He had been afforded the chance to watch four consecutive ECAC Hockey championship teams and two NCAA title teams. His final year at Cornell coincided with Cornell's claiming the only national championship-winning undefeated, untied season in NCAA history. Hockey had become part of his essence.

The doctoral recipient shortly made the trip that no Cornell hockey team had. Hendry received a position at the Pennsylvania State University following his graduation. Cornell and Penn State were among only a handful of institutions to offer tenured faculty positions in Organic Chemistry in that era. The graduate expected to find hockey at Penn State. He would not. He began to notice leaflets that inquired why Penn State did not have hockey.

Hendry became the faculty figure to whom students who desired a hockey program at Penn State turned. The students were the impetus, but Hendry was the facilitator. The Cornell graduate and his Penn State undergraduate backers met administrative resistance. Hendry was not alone with his ECAC Hockey connections.

Dick Merkel, an alumnus of St. Lawrence University and the Pennsylvania State University, joined Larry Hendry as a faculty member who pushed for hockey at Penn State. Hendry and Merkel were shocked that an institution of 1,600 students like St. Lawrence could be a traditional power that filled its arena while Penn State with 23,000 students at the time had no program at all.

Hendry and his associates did manage to establish a hockey program. The group created the Penn State Hockey Club in the Fall of 1971. The Club drew so much attention that its members needed to be subdivided into pseudo-varsity and -junior varsity statuses. Many members counted Pennsylvania as their place of origin. Hendry noted that the team was far from exclusively Pennsylvania, "some veterans turned mentors were from rabid hockey bastions in Minnesota, Massachusetts and upstate New York." Some players hailed from Canada while others had previous playing experience at institutions like St. Lawrence.

Penn State had a team in its group of players of variable seasoning. The Icers, as they would become known, had a coach in Larry Hendry. They needed guidance and equipment.

The first jerseys in which the Penn State Icers played were provided by Joe Paterno. Worn or unneeded football jerseys served as improvised hockey sweaters when Hendry's Penn State team first took the ice. Those familiar with the history of the Icers know that Hendry's Dodge Dart returned from Pittsburgh with equipment that the Pittsburgh Penguins donated to jump start the program. What few know is another trip that his Dodge Dart took.

Larry Hendry had jerseys, some pads, and some skates. He needed other equipment. Specifically, he needed a supply of sticks. He may have needed some guidance also. The recent graduate of Cornell University decided that he would return to familiar territory for both. The Dodge Dart took him on the familiar route back to Ithaca.

Accounts differ with whom Hendry interacted at Cornell. Some claim that Ned Harkness remained his point of contact at Lynah Rink. Harkness had moved on to coach and manage the Detroit Red Wings by Fall of 1971 which makes it more likely that Dick Bertrand was the Cornell coach who assisted Hendry. However, Ned Harkness did maintain a home in Ithaca to serve as liaison for Cornell hockey during the transitional period that followed his departure.

Nevertheless, Hendry returned to Penn State with sticks that were given to him either at cost or free of charge. The first twigs in the foundation of the modern era of Penn State hockey came from Lynah Rink. With an improvised array of equipment, Hendry began his first season. He received something else from Cornell. A pledge of support and exposure that might have proved more lasting than the sticks that scored the first Icers's goals.

The team was grateful to Hendry. The Icers returned college hockey to Penn State during the 1971-72 season. Penn State, an institution that seeks to compete against the best, began to grow uneasy with its status as a club team even in the Winter of 1972. Students and players began to state that their goal was to gain admission into ECAC Hockey. The two schools that lured them to that conference were Boston College and, predictably, Cornell.

Cornell hockey's support of Penn State hockey came in many different forms. Few remember this reality, but Lynah Rink served as a host to the Penn State Icers at least twice during the 1971-72 season. On February 19, Penn State played Ithaca College at Lynah Rink. The title of Bombers may have been more appropriate for the Icers as the latter dropped the contest, 13-2. The more interesting reality is what Icers players learned a few days later.

Alumni of some of the first Penn State Icers squads recall how Cornell graciously allowed them to attend a contest at Lynah Rink. Bertrand's stated purpose for doing so was to expose the Penn State players and uninitiated coaches to what a college-hockey atmosphere could be at its best. The contest to which he invited them was the February 21, 1972. It was the Harvard game. Penn State already was in town.

Nearly two decades before Michigan hockey would repurpose and modify Cornell hockey's famed chants at Yost Ice Arena, Penn State hockey players were exposed to them as spectators on wooden bleachers in Lynah Rink. Importantly, it was the senior year of Neil Cohen. Cohen was not a player. He is the member of the Lynah Faithful celebrated for bringing the cowbell from the pasture into the Rink.

The blaring band, the clanging cowbell, the aggressive attendants, and the seething loathing between Cornell and Harvard left impressions on even the mostly disinterested Penn State Icers. Elenbaas registered 34 saves and showed what is expected of a goaltender of the highest calibre. Some Icers still recall the relentless harassment of the Crimson's Bertagna. The Lynah Faithful ensured that Cornell never trailed. The Big Red won, 5-2, with a hopeful group of Penn Staters in the stands. That group imagined what Penn State hockey could become.

The Penn State Icers missed the germinal fish throw by one installment.

Penn State would play at Lynah Rink on December 16, 1972 during the next season. The Icers would lose again to Ithaca College. There is no indication that the Icers were invited to attend Cornell's contest against Boston University that occurred six days prior. The first great composure to Cornell hockey remained.

The hockey team of Penn State lost its on-campus home rink in 1978 when it became an indoor practice facility for football. It took the University three years to give the Icers an on-campus home. The Greenberg Ice Pavilion opened in 1981. It would serve as Penn State hockey's home through the dominance of the Icers, the creation of the ACHA, and the first season of NCAA Division I hockey.

The Pavilion contained one side of seating. Teams entered the ice walking from their locker rooms across the back side of the boards at one end of the ice. There, fans could heckle or support teams as they looked over the edge at the players filing onto the ice. A walkway extended from atop the stands at the opposite end of the ice to the rink's exterior wall. The capacity of the Ice Pavilion was a mere 1,200 people.

The plans for the building contained one interesting architectural detail. The wall opposite the 1,200 seats was non-weight-bearing. The plans for the Greenberg Ice Pavilion left open the possibility that if Penn State hockey continued to draw well, the external wall could be removed for additional seating. Such an expansion was expected to coincide with an elevation of the Penn State Icers to NCAA Division I. College-hockey fans know that no such expansion ever and no elevation occurred without the promise of Pegula Ice Arena, but imagine the shape of the Greenberg Ice Pavilion if it had expanded. Its atypical horseshoe-like shape would seem familiar to the Lynah Faithful.

Lasting Connections

The interplay between Cornell and Penn State has been important to both institutions. It was Ned Harkness or Dick Bertrand who ensured that Larry Hendry's first squad was equipped. It was Dick Bertrand who gave the first large group of Penn Staters its first exposure to an elite college-hockey atmosphere. It was a Penn Stater in attendance who chose to imitate Neil Cohen's characteristic clanging of a cowbell months later at Beaver Stadium which gave rise to a tradition in Penn State's preeminent pastime. It was the respect born between two programs from schools with similar missions after a result that should have imbued little. It was the near misses in the early 20th Century. It was the ways that Penn State drew upon Cornell as a model of perfect integration of classical and modern education. It was the way that Penn State's savior saved the legacy of Ezra Cornell first.

The interplay has been long lived. It extends beyond athletics. It has touched the identities of each institution.

Special recognition is owed to Kyle Rossi. His work while Thank You Terry was published made Penn Staters and college-hockey fans aware of the proud and deep history of hockey at the Pennsylvania State University. None of the information within this post regarding the records of Penn State Icers teams or the venues that Penn State called or endeavored to call home would be possible without his considerable efforts. Additionally, his narrative of the history of Penn State augments and informs much of the narrative that this writer uses in comparing and contrasting hockey at Cornell and Penn State. Thank You Terry and he remain the best resources for Penn State hockey history.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed