Legends Etched in Ice

Allegheny, PA, a community located just outside of Pittsburgh but no more immune from the city's cultural sphere than it was proximate, did not experience ice hockey firsthand until 1899. The Vincent family's general affinity for Western New York, Buffalo, in particular, might have provided earlier opportunities for the family to observe the sport that would make its son famous. Exhibitions brought the sport to the Steel City inconsistently. It was the construction of the famed Duquesne Gardens that began the love affair between Pittsburgh, hockey, and the son of one of its cherished environs.

One can imagine a young Jefferson Vincent attending the opening weekend of Andrew McSwigan's lavish hockey hall. A ten-year-old boy watched, unrealizing what the sport would come to mean to him and many others because of him, as Canadian and a few American professionals demonstrated the smoothness and abruptness of this new game. It might have been either the guiding hands or insightful comments of one of these players or coaches who came to live in Western Pennsylvania and who would win eventually the Stanley Cup on multiple occasions that helped Vincent become a phenom just eight years later.

The bustling scene that was a roaring Pittsburgh created the obfuscation that was Jefferson Vincent's workshop. He would be very active below the surface and then would make tremendous gains when he wanted to be noticed. His youth would be no different. Clouded remained his time in Western Pennsylvania.

Jefferson Vincent's path meandered eastward. The boy whom hockey transfixed was enrolled at Mercersburg Academy. The Academy was a fine institution in preparing Vincent for eventual collegiate studies at the nation's finest institutions. Its location, closer to Maryland and farther from Pittsburgh and Buffalo, proved problematic to sharpening the Allegheny native's interest in hockey.

Mercersburg Academy had no distinguished history of ice hockey. The invitational series at Duquesne Gardens informed Jefferson Vincent by analogy of which universities had developing traditions of college hockey. His gaze narrowed on the land-grant university of New York. In 1906, Vincent graduated from Mercersburg Academy. Boarded and prepped, he was ready to move on to greater challenges.

The Western Pennsylvanian traded one bustling town for another. Hockey was the constant. Hockey came to Cornell University in 1896, three years before it had a stable presence in Pittsburgh. Seasons of intercollegiate competition for the hockey team from Cornell University began in 1900. As a freshman in the College of Engineering, Jefferson Vincent yearned to don a carnelian-and-white sweater.

The fog of an early winter's morning lifted off of Beebe Lake much as one would lift around the life of Jefferson Vincent as his skates cut through newly hardened ice. He would make the freshman team. It was with Vincent as a forward that the freshman squad began to have impressive showings against the varsity squad for the first time in the history of Cornell hockey. His talents were neither lost on the varsity's captain, Ralph Lally, nor limited to hockey.

Jefferson Vincent was a born leader. A dedicated head coach had never led Cornell hockey through four seasons of intercollegiate competition. Cornell had never played more than three games in a season. Vincent knew that neither was sustainable for a program in which he saw the germs of greatness. Lally and Vincent agreed that Vincent would be a player on the freshman roster while serving as manager of the varsity squad.

As a manager, Jefferson Vincent served as a coach during practices and negotiated future contests and scheduling with the programs of other universities. The Cornell varsity team registered its first win in four years during Vincent's first season as manager. Cornell played its fullest slate of games in the forward's second season as manager.

Many programs dickered with Cornell hockey in its several seasons of existence. It was Vincent who proved able to negotiate the closing and performance of deals. These traits served him well in his years after leaving East Hill.

Yale, after a six-year absence from Cornell's schedule, returned as a regular fixture. Dartmouth began its series with Cornell in just Vincent's sophomore year as manager. Jefferson Vincent brought enough acclaim to his program that during his third season as manager, Cornell became a perennial invitee to Cleveland's early-season tournament at Elysium Arena, the unofficial opening of the collegiate season in that era.

Vincent's adeptness at coaching and negotiating did not overshadow his playing career for the Big Red. He earned his way seamlessly onto the varsity roster in his second season at Cornell University. The sophomore forward led his carnelian-and-white cadre to an undefeated season. The 1907-08 Cornell hockey team never allowed a goal. It scored 21 goals in just four games.

One of Jefferson Vincent's highlights from that season was his key role as guarantor of a perfect season with his contributions to the utter dismantling of the team from the University of Rochester. The emergent sophomore star showed little remorse in helping his alma mater defeat one of the programs from the region that he soon would call home. This callousness might have been necessary. As manager and without the assistance of a professional coach, Vincent converted the two undefeated seasons that he managed into an invitation to the Intercollegiate Hockey Association. His beloved program was now eligible to compete for national championships.

Vincent's lone failure during his time as manager of Cornell hockey was an inability to get Harvard's hockey team to do more than negotiate with the team from Cornell University. It appeared that Jefferson Vincent was about to close such an arrangement many times. Harvard reneged each time. An invitation to the IHA did not allow the Crimson to dodge the Big Red for much longer.

Vincent was a standout on the ice during Cornell's first season in the IHA. There were few others. The icers from East Hill finished the season with a losing record. The only team that Cornell defeated was Penn. The national championship that seemed so close at the beginning of the season drifted further out of reach. Worse news would come soon after the season resolved.

Extenuating circumstances in Jefferson Vincent's life required that he take a leave of absence from Cornell University during the 1909-10 academic year. During this time, he began to identify as a Western New Yorker and Buffalo native. One can assume that situations forced his family, likely his mother, to relocate to Buffalo. The opacity in which Vincent always found great comfort created uncertainty about what caused his absence.

Cornellians who loved their hockey program and those associated with that program knew how great a loss it was for the team. Jefferson Vincent was so well conditioned, which one could expect of an athlete who was a star on the cinder, that no one ever substituted for him. It would require several players to account for his ice time alone. His skill was unmatched. No one could be expected to play like he did. The Cornell Daily Sun summarized the loss well in saying that "there will be a much larger opening for competitors" who hoped to make the team.

In the Fall of 1910, nearly four months after Jefferson Vincent expected to graduate, he returned to Cornell University. His Beta Theta Pi fraternity brother, Malcolm Vail, became a fan favorite of Eastern hockey fans as one of the nation's best goaltenders during Vincent's absence. The program that Vincent helped build had changed.

December 5, 1910 marked the beginning of hockey practice for Cornell. Each player had to earn his way back onto the Big Red's roster. The task was more difficult for Jefferson Vincent after a year's absence. Vincent strode onto the frozen water of the lake he knew well. He had led many practices on this ice. However, opposite his teammates and him was Talbot Hunter, the first head coach of Cornell hockey, who took over coaching duties during the senior's hiatus.

Hunter was an import from Canada who knew little of the college game before Cornell University hired him in 1909. He knew nothing of the skill and fanfare that accompanied Jefferson Vincent. It all would need to be reproven.

The student fans who watched practice were impressed with Vincent. Many identified him as the player who stood out most. Evidently, Talbot Hunter was not as impressed. Developments over the remainder of tryouts would bear this out. Vincent always survived each cut, but Hunter remained unimpressed. Practice did not relent, drill after drill, through inclimate and miserable weather. Scrimmages tested his candidates regularly. Vincent endured.

The penultimate cut occurred on December 12, 1910. The list of candidates had been whittled down to 14. The final test would be a seven-on-seven, full-length scrimmage. The first team was populated with players of the skill level of Edmund Magner, star center, Frank Crassweller, all-American rover, and Malcolm Vail, nationally renowned goaltender. Its roster was the expected roster for Cornell in the 1910-11 season. Jefferson Vincent found his name on the second team.

Vincent, of relatively humble means, always personified the yeomanly ethic of industrial cities like those of Pittsburgh and Buffalo. Most star players of any rank would be irate at such a snub. The senior forward focused. He harbored no apparent resentment. He knew that his second team was less talented and less prepared, but he would do what was required to show his worth.

The second team lost by a 7-2 margin to the talent-flush first team. Crassweller was the highest scoring player in the game. Something nearly mystical happened during the contest. The Cornell students who for over a decade sated their ravenous hockey appetite by watching practices bundled along the boards of Beebe Lake knew that they witnessed something that few ever would witness in their lifetimes. Talbot Hunter did as well.

The game drudged on at times with an ominous sense that the first team would win. Never surrendering, Jefferson Vincent battled along his boards and in his half of the ice to try to intercept Crassweller and Magner. He played equally hard in the offensive and defensive ends. Then, his aura reappeared. Vincent rangled the loose puck. He skated stride for stride at Crassweller at center ice. The first team's defense collapsed around him. Jefferson Vincent capitalized on the action and confusion, and did what he did best. He disappeared.

He evaded the inevitable checks of body and stick. The puck glided smoothly through the blockade. Vincent collected the puck on the other side of the bedeviled defenders whom he split. A quick strike beat the nation's best goaltender.

The senior would style another moments later. The two goals that the second team scored were his tallies. Vincent's defensive efforts were not enough to win the scrimmage, but he did earn the respect of his coach. Jefferson Vincent was the only player from the second team in that scrimmage to make the final roster. His talent was self-evident, but never assumed. He earned everything.

Vincent rewarded Talbot Hunter's trust in him. The coach continued to expect great things out of his star winger and push him along with his team tirelessly throughout the season. The combination of Vincent and Magner became special. The two combined for three goals in the first half of the first game of the collegiate season. The second game, like the first, against Yale, witnessed Vincent's first career hat trick at the Chicago Ice Palace. Cornell alumni in attendance and teammates on the ice succumbed to raucous jubilation. The Cornell star was just getting started.

A hat trick against Yale in the second game of a three-game series was not the end of the senior-year dramatics for Jefferson Vincent. The IHA tournament to decide the eventual national champion opened on January 14, 1911 against Princeton. The increasingly famed winger wasted no time. Vincent opened scoring within seconds. Few opponents fared better.

Yale met Cornell for the fourth time in the season during the IHA tournament. The Western New Yorker made sure the Elis realized that their fate in Manhattan would be no different than it was in Chicago. The aggressive Bulldogs peppered Vail in the early seconds. Vincent forced a turnover and did what he did best on a breakaway. The resulting goal demoralized Yale. Columbia was equally dejected when Vincent scored very early, twice.

The ability of Jefferson Vincent to respond at will was known well in the IHA. Opponents who dared to tighten games during the 1910-11 season did so at their peril. Close games were evidently unacceptable to the senior forward. Yale was allowed to get within a 2-1 margin of an eventual 4-2 defeat and Dartmouth was afforded the proximity of only a 3-1 differential in an ultimate 5-1 defeat. Lightning speed and watchmaker-like precision accompanied the clinics that followed each as Jefferson Vincent rewidened margins.

No goals were more consequential in his career than those that he notched against Harvard at the year-old Boston Arena. The ice surface of the new arena was 60 feet longer and 20 feet wider than the other rinks at which Cornell played. The spaciousness became Jefferson Vincent's plaything.

Collegiate and national media billed the Cornell-Harvard game of January 28, 1911 as the decisive contest in the IHA tournament. It decided the national champion. The IHA tournament was a round-robin tournament. The pedigree of both Cornell and Harvard left many believing that the only team that had the discipline, talent, and teamwork to defeat one was the other. They were right. Vincent did not toil for years to garner Cornell the opportunity to bring a national championship to his alma mater to allow it to slip through his fingers during his last chance to deliver it.

An unassisted breakaway began the end for Harvard. Jefferson Vincent's hiatus from the University prevented his making an impression on the Crimson in the first meeting between the hockey programs of Cornell and Harvard. He compensated for lost time. Harvard thought he overcompensated.

The game was the closest of any game during the 1910-11 season. The Cantabs forced the Ithacans into overtime. Crimson hopes of a national championship lived at the prerogative of a Western New Yorker. History proves that is the most dangerous balance for the hopes of Harvard.

Magner and Vincent eroded Harvard on the Crimson's own ice in overtime. The star center maneuvered. Vincent vanished into the space-between that only he seemed able to find. Harvard lost Vincent. Magner connected to the legendary winger. The shot unleashed required the tensile strength expected of a player raised near the Steel City as it threaded its course into Harvard's twine. The expanse of Harvard's ice surface at Boston Arena foreclosed the Crimson's championship hopes when Jefferson Vincent came to town.

Talent is the metric by which all greats are compared. The first game of the 1911 IHA tournament proved how talented Cornell's senior winger was. Kay, the rover and captain of Princeton, was viewed as one of the greatest players in the nation. The reputation of only one rover surpasses that of Kay in the history of Princeton hockey. Many were not certain how Vincent would match with an offensively talented rover like Kay.

Jefferson Vincent corralled Kay into Princeton's defensive zone. Kay rarely enjoyed the puck on his stick. When he did, it was not long until Vincent retrieved it through fine stick work or clean checking. Vincent consistently employed effective forechecks and backchecks against all opponents. When opponents attempted aggressive backchecking against the Buffalo native, he evaded. Dartmouth players even knocked themselves unconscious in their frustrated and futile physical salvos to slow the senior marvel.

Extraordinary vision allowed Vincent to find other carnelian skaters when the defensive tactics of the opposition became too concentrated on him. Vincent contributed the primary assist on many of the big goals of the season that he did not score. Crassweller's go-ahead goal against Yale and Magner's second goal against Harvard stand as examples of this intelligent, unselfish style of play.

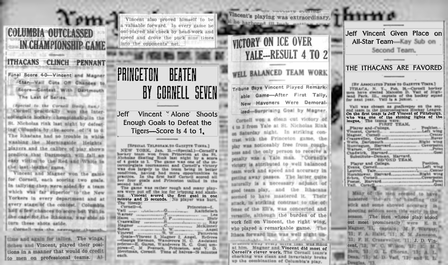

The skill of Jefferson Vincent was uncommon. It was generational. It was no surprise that the media fell in love with him. The understated, somewhat aloof star was an atypical headline-generator. This did not stop the national sports journalists of the era. Periodicals including the Boston Herald, Boston Journal, Boston Evening Transcript, Gazette Times of Pittsburgh, New York Press, and New York Tribune filled reams with praise for Cornell's wunderkind.

The consensus was "...Vincent, played [his] position in a manner that would do credit to men on professional teams." The Tribune summarized that "[Cornell's] attack...was concerted and versatile, although the burden of the work fell on Vincent, the right wing, who played a remarkable game." The local Press was not to be outdone, "[t]he big, rangy Princeton players were bewildered by the speed of and elusiveness of...Vincent." The Evening Transcript once commented that "Vincent did most of Cornell's clever work."

Pittsburgh and its media loved their favorite son who went off to perfect college hockey in Central New York. Headlines and stories in the Gazette Times boasted "Jeff Vincent alone shoots enough goals to defeat the Tigers" and "Jeff Vincent of Pittsburgh...was one of the shining lights of the league." Neither national intrigue nor hometown favoritism limited the reach of Jefferson Vincent's appeal while wearing the carnelian and white.

Cornell students and alumni reveled in watching Vincent decimate opponents. The Cornell Daily Sun reported the emergence of this phenomenon in Chicago and Cleveland. "[T]he team was warmly received by the alumni and undergraduates who packed the houses at each contest." "[T]he crowd marveled" at the impressive play of Jefferson Vincent and his teammates. These events marked the beginning of a trend that lasted generations.

Fans, aligned and unaligned, began to frequent college-hockey games in which Jefferson Vincent would play. They wanted to capture a glimpse of the spectacle that was this American-born hockey player. Increased ticket prices accompanied games involving Jefferson Vincent. Venues did not remain listless long when Vincent took the ice. Costs of entry to the Cornell-Harvard game during the 1910-11 season ranged from $1.00 to $2.00. Those tickets adjusted for inflation would cost as much as $50.00 today.

Exorbitant costs of tickets were not the only novel accompaniment of that Cornell-Harvard game. As loved as Jefferson Vincent was among Cornell fans, students, and alumni, opposing fans loathed him proportionately. Jefferson Vincent on that evening in Boston elevated Cornell to a level in the Crimson mythos that no rival has been able since to reach. The moment that Vincent outwitted Chadwick in overtime for the national championship-clinching goal, a monsoon of massacred rabbits blotted the ice; the first debris of a littered rivalry.

Whether fans harbored incensed ire or calamitous celebration, there was no denying that Jefferson Vincent drove fans to the stands and then brought them to their feet. His name might never have graced a marquee in front of an arena, but promoters knew the effect that his presence on the ice had on the scale and allure of their events.

Vincent's adopted hometown of Buffalo was the City of Light, but he dreamt never of seeing his name in lights. The senior winger from Western Pennsylvania and Western New York neither demanded nor sought the glow of a spotlight. On a team of stars of the calibre of Crassweller, Magner, Scheu, Warner, and Vail, Vincent stood out. Jefferson Vincent was greatest among greatness. He reflected the glow of his acclaim and accolades upon his teammate.

The Cornell Daily Sun was the most frequent observer of this reality. The greatest strength of the 1910-11 team was its idyllic "lack of the 'grand stand' player" which made the hockey team "[a] fit example for any major or minor team of the University," according to The Sun. The cohesion of Talbot Hunter's second team and the humility of its most talented player were related not coincidentally to its perfect 10-0-0 record.

No team in the pre-NCAA era had a talent so great and nationally recognized as Jefferson Vincent while still completing a perfect season during that player's tenure. The character and leadership of Vincent were of historic proportions. Jefferson Vincent became what his team needed when it needed it.

No official recorded a penalty against him in his career because his play was so refined in every situation. Over his four years competing at Cornell, he played in three different positions. He played as a center and left wing when his team needed even though his natural niche was along the right flank.

Fred J. Hoey of the Boston Journal exploited comically Jefferson Vincent's versatility when he was filling his all-American roster. The syndicated hockey columnist chose Vincent as his first left wing on his all-American team. The Beantown journalist argued that egalitarianism required such a move. The play of Vincent so dwarfed that of all other right wings in the nation that he demanded choosing.

The field of left wingers was less talented and allowed Hoey to choose a respectable player as the right winger who deserved recognition. He comforted his readers, "Jeff Vincent, Cornell's right wing, can shoot from either side and with this advantage could well be placed on the left wing."

Selflessness and loyalty do not entomb the reality that Jefferson Vincent was the first great American-born hockey player. Vincent remains one of the greatest players in the history of Cornell hockey. The first game in which he showcased, the January 1908 contest against Rochester, was the last time that Vincent would play center. Mistakes were made. It was the last game in which Jefferson Vincent would score only one goal.

Jefferson Vincent averaged scoring 2.11 goals per game over his career. Only one player in the modern era of Cornell hockey has been even within one goal per game of that total. Doug Ferguson produced consistently at a rate of 1.11 goals per game. All-time leading goal scorer Brock Tredway tallied only one goal per game. Greats like Joe Nieuwendyk, John Hughes, Lance Nethery, and Matt Moulson register at 0.90, 0.87, 0.82, and 0.53 goals per game, respectively. Cornell never has seen a player who resembles Vincent in the modern era despite all the dominance its fans have witnessed.

The production of Jefferson Vincent is handicapped additionally. He played in an era when it was not uncommon for games to be truncated to or called after 30 minutes. He scored over twice as many goals per game as Cornell greats during games that were sometimes half as long.

The national championship-clinching goal against Harvard and the game-winning goal against Dartmouth that guaranteed a perfect season both belonged to Jefferson Vincent. Vincent never scored fewer than two goals in any contest throughout the IHA tournament. The stealthy right winger delivered when it was needed most.

Jefferson Vincent never entertained the prospect of playing professionally. The pinnacle of his hockey career was guaranteeing a national championship for Cornell University in guiding what was then the winningest perfect season. He achieved his goal. The hockey program of the land-grant university of his adopted state now stood as the bar by which other programs were judged. Vincent, a student who was so restive as to study both mechanical and electrical engineering while delving deep into liberal-arts curricula, focused on service beyond that which he could do with his athletic abilities. Graduation approached. Honorifically, he became a graduate of the Class of 1910.

Grazing the Face of God

Seated in the Armory for the University's 43rd Commencement, President Schurman addressed an assemblage of Cornellians who would come to embody the best of Cornell University's ideals and become its greatest generation. The message of the moment was clear. Governments will not solve society's ills. It is the task of the individual to change the world around him.

"All great reforms are the work of individuals...reformation that is worth anything must be enacted in the hearts and minds of individuals." As if scrawled into a script, these words would animate the graduates. The athletic paragon who excited his fellow graduates, peers, and alumni became that individual who dared real reform.

A yeomanly undertaking carried Jefferson Vincent from the unassuming shore of the Allegheny and Ohio Rivers to one of the world's finest academic sanctuaries, allowed him to endure undeterred a disruption in his studies, and fashioned him into the greatest American-born hockey player. His next feats would be his most miraculous. Scoring goals against Harvard and inspiring undefeated seasons would pale in comparison.

As obscuring as the early settling of twilight on the ice of Beebe Lake after the hockey practices Vincent knew so well, the Cornellian skater deflected credit in shrouding his activities from the public eye. The bark of Talbot Hunter directed him no longer. It was the call to serve his nation that took its place.

The trained engineer proved versatile in his skill. Vincent wielded the lessons of Cornell University's cultural empathy and interdisciplinary ethic as tools in serving the American people. A fluency in Spanish served well Jefferson Vincent as he was drawn away from his expected career path in engineering to the consular service of the United States. His postings proved to be essential for the commercial, diplomatic, and military interests of the United States in years before the nation was thrown into the grips of the First World War.

Jefferson Vincent's diplomatic career began in the American consulate in Chile. It was his later appointments to Spain and Italy as an emissary of the United States that he first filled the role of national hero. Vincent's successful Spanish diplomatic encounters occurred in the wake of much tumult.

His contributions to another consular effort were no less impressive than his oft-highlighted Iberian efforts. The alumnus of Cornell University served two missions of the eventual foreign service in prebellum Europe. American consular servants feverishly labored in Rome to circumvent peninsular involvement in the First World War when the conflict broke. It was no small task to persuade Italian officials that their nation needed not honor a defensive pact with the German Empire.

This victory of Jefferson Vincent and his diplomatic colleagues was short-lived. Italy entered the war nine months after hostilities opened. Greater success accompanied Vincent's contemporary service in Spain. It was the Cornellian's accomplishments with Madrid that encapsulated the highlight of his consular career.

The Cornellian and his cohort were only ten years old when the hostilities of the Spanish-American War ceased. The gashes of that conflict still demanded tending. Jefferson Vincent massaged the relationship between the once-belligerent states. The agitations of war on the horizon from an expansionist German Empire uneased those in Washington who still romanticized American isolationism. Normalizing relations with a traditional trade partner of the United States guaranteed commercial benefits for American industries and Americans on the eve of war.

Defused of much stress after several rounds of trade agreements, the United States gained considerable leverage in encouraging Spain's natural inclinations to remain neutral when the First World War began in 1914. Exchange with the markets of the yet-unaligned United States allowed Spain to reap financial benefit without recourse to war. American diplomats aided their Spanish counterparts in navigating the complexity of being a commercially active, unaligned state during the outbreak of the first modern world war.

Vincent traded dodging rovers and defenders, and converting threaded-needle passes from Magner for helping foreign states in search of peace navigate the troubled waters of war. The Buffalo native served in the great tradition of Cornell-affiliated diplomats, such as no less an influential figure than Andrew Dickson White. As all true great citizen-diplomats before him, Jefferson Vincent recognized that when the desired instruments of peace fail, resort to the instruments of war to defend sacred values is necessary.

Heroic embrace of this hallowed duty left the general public and the community of Cornell University with one last paradox. The former hockey forward absconded from his diplomatic service when American involvement in the war became inevitable. The born Pennsylvanian who came of age outside of Pittsburgh, whose family in part called rural Illinois home, and who became the consummate New Yorker of his adopted Western New York etched his last great mystery with his enlistment.

Perhaps it was connections that he developed along the Pacific Coast of the Americas during his service in Chile. Perhaps it was an overwhelming urge to serve his country that overcame him while he was visiting a distant state. Curiously, in 1917, Jefferson Davis Vincent entered the service of the United States Army from California.

It was not Vincent's first foray into military exercises. Fulfillment of Cornell University's land-grant mission required all able-bodied males to receive military drilling and instructions in the military sciences. Vincent was an active member in the signal reserve corps of the United States Army. The former hockey manager was a trained officer of the American military. The proud and dedicated reservist received his commission shortly.

The various branches of the United States Signal Corps began to be folded into complementary roles within the United States Army as the home of the Aviation Section of the American military as early as July 1914. Dual roles of reconnaissance and aerial combat made sense of this uneasy union.

The speed, precision, and daring that typified Jefferson Vincent in the glowing columns that dried barrels of ink from Chicago to Boston during his hockey career found even fewer limits during wartime. Vincent became a winger in a literal sense. He served with the 24th Aero Squadron.

Lieutenant Vincent first reported to San Diego for preliminary training. His particular aptitudes and recognizable intelligence led to his recommendation to the Army's flight school at the University of California. The carnelian-and-white star devoured the curriculum at California's land-grant institution. He would join the unit to which he was commissioned at Kelly Field in Texas soon enough.

The grizzled veteran of college hockey stepped foot in San Antonio with the ambition to be a leader of fellow men and defender of his nation. Only two percent of servicemen during the First World War were commissioned. Vincent represented his alma mater proudly in rounding out the 60% of Cornellians who garnered commissions. The Western New Yorker would achieve his goal.

Vincent's 24th Aero Squadron awaited deployment to the European theatre from Long Island by the end of the calendar year in 1917. The miracle completed at St Nicholas Rink, under 30 miles from his base in Long Island, nearly seven years before might have brought momentary quietude to his mind. Jefferson Vincent bade adieu to his beloved adopted home state in January. He would not return.

The 24th Aero Squadron arrived in Great Britain and continued its training. The unit awaited its orders to move to the Front. They would come in May 1918.

The United States had been nominally at war with the German Empire for over a year. A preliminary step toward any successful repulsion of the German forces from France required ample intelligence. The 1st Army Observation Group would meet that need. Its constituents were the 9th and 91st Aero Squadrons, and Jefferson Vincent's 24th Aero Squadron. The 24th Aero Squadron joined the more seasoned 91st Aero Squadron in France.

The 1st Army Observation Group gathered gradually on the Toul front at the Gondreville-sur-Moselle Aerodrome. This base of Vincent's aerial operations was just 16 miles from the Western Front. The region had known intense combat throughout April. The constant threat of bombardment loomed over the airbase. Two concerted German aerial efforts would greet the 24th Aero Squadron to France in the summer months. The sprawling layout of Gondreville-sur-Moselle intentionally rendered it less susceptible to catastrophic raids.

It was this layout that undermined unit cohesion. Stationed servicemen resisted the dint on morale with trips through neighboring French villages. These American flyboys and intelligence officers became an attraction. Few could engross themselves as well as could the urbane Jefferson Vincent. Despite not entirely unexpected newfound celebrity, Vincent and his squadron knew why they were in unfamiliar territory.

The 1st Army Observation Group near Toul included embedded intelligence officers and sophisticated photographic labs. Both of which were necessary in drawing reasonable conclusions from the reconnaissance born of the pilots's daring. The skill and courage of pilots like Vincent certainly were required.

The pilots of the 1st Army Observation Group flew French Salmsons type 2A2 aircraft. The Salmsons had a very limited fuel capacity and were not well suited for the high-altitude flying that penetrating reconnaissance sometimes required. The typical scouting flight occurred at altitudes between one and three miles. More accurate aerial photography and cleverly concealing German tactics made the best pilots maneuver their crafts at heights around 600 feet, exposing themselves to anti-aircraft fire. Jefferson Vincent was such a pilot.

The 24th Aero Squadron had many distinctions. It was among the first wholly American-trained flying divisions in the history of the military of United States. It was chosen to enter the European theatre because it was regarded generally as well trained. Nevertheless, only select pilots were allowed to engage in activities other than training alongside the 91st Aero Squadron in the first few months along the Western Front.

This requirement for seasoning did not erase the necessity for better intelligence in mounting any offensive to repel the Germans from France. Probing and frequent observation was required. There was inadequate reconnaissance of German entrenchment from which to devise a plan of attack before June 1918. Photographic scouting missions penetrated deeply behind the Front to record German rear movements and artillery capacity. Pilots and photographers in the two-seated Salmsons relayed observations to Gondreville-sur-Moselle. Information would not perish, even if they did.

There was little known of German assets and abilities to outflank or counterstrike. Early observations were quintessential to what would become the St. Mihiel Offensive and the eventual ejection of the Germans from France. The need for frequent missions collected its toll on the fleet of aircraft. France's industrial base was ravaged and it was ill-able to keep up with the demand of quality that France's American protectors needed. By the second week in May, it was widely known along the Front that France was producing inferior propellers for its Salmsons.

The pilots of the 1st Army Observation Group, including Jefferson Vincent, recognized this reality. They elected to continue their scouting and training missions at the risk of their own welfare. They had a war that they needed to win and ground forces who would need the invaluable resources that the pilots's courage unearthed.

May 3, 1918 marked the 30th birthday of Cornell hockey's greatest legend. He celebrated it 3,500 miles from home. The lessons of his time at Cornell University, as an exemplary student and a hockey star, had not left him. He realized that considerable ardor and tireless labor were the only means by which one could perfect a skill. The hours on Beebe Lake, overworking and overachieving under Talbot Hunter so that when the moment arrived to perform, the task at hand would seem easy even if few ever could even fancy replicating it, guided Vincent. That was hockey. This was more important. His service in France was his greatest undertaking.

Tireless was Jefferson Vincent's work ethic. His orders for his anticipated role in the coming Battle of St. Mihiel laid in his quarters on May 14, 1918 when he left for training exercises. A week of inclimate weather grounded his preparations. He would not be denied the opportunity on that clear day.

Vincent planned to do practice scouting and strafing runs on targets. Realizing on previous scouting runs that German units concealed their locations and endeavoring to provide his countrymen with the best information possible, the Cornellian planned to practice entering a nose-first, spinning dive to reach lower altitudes at considerable speed. These tactics bore the ripest fruits for his fellow servicemen.

Jefferson Vincent climbed into his aircraft. He gave a thoughtful nod, like those he had given raucous Cornell alumni in Chicago, New York, and Boston, as his plane roared to life. As elegantly as he skated for his adoring fans and as capably as he served his nation as diplomat, Vincent soared into the horizon and the fading sun. He vanished.

Forever, A Humble Hero

Jefferson Vincent was laid to rest. In a tremendous show of respect and remembrance, the collegians of the 1st Army Observation Group elected to serve as the patriot's ultimate escort. His final place of rest was St. Mihiel American Cemetery. College hockey and Cornell University lost a favorite son.

He was not the only son whom Cornell University lost in the First World War. More Cornellians served than did the alumni of any other institution of higher learning in the United States, including the service academies. 264 of those Cornellians who served gave the last full measure of devotion.

Nearly 16 years to the day after Edmund Magner directed his last assist to Jefferson Vincent, he would deliver one final assist to his departed linemate and friend. Buffalo and military service united Magner and Vincent. The former star center was a key member of the committee that conceived of and raised funds for the War Memorial. A timeless monument to the values and courage of Cornell's greatest generation and bravest souls rose from the earth of West Campus. A very personal motive partially animated the actions of Magner as he assisted in remembering his fallen peers. Not the least of which was Jefferson Vincent.

Cornell University marked its gratitude to its greatest generation on June 8, 1919. President Schurman, whose words motivated Jefferson Vincent nearly eight years prior, read the honor roll of the then-known 206 people associated with Cornell University who perished in the conflict. Major General Robert Alexander of the United States Army delivered a eulogy to the capacity crowd at Bailey Hall.

Major General Alexander proffered a metric by which one's service can be measured. He reasoned that commissioned officers, those tasked with leading their fellow soldiers, are the determinative factor in any modern war. Thoughtfulness and thoroughness discern an officer's merits. "Unless he knows his business, we will incur the risk of defeat and the uncertainty of undue loss," concluded Major General Alexander.

First Lieutenant Jefferson Vincent's service was distinguished by these metrics. His 24th Aero Squadron took center stage when the St. Mihiel Offensive began. Nearly continual engagement in combat and reconnaissance missions along the Toul and Verdun fronts reflected well upon the departed Cornellian. Vincent's unit was distinguished for its uncanny abilities and steeled resolve to gain intelligence even in the most dangerous of circumstance. There was no greater homage to one of the 24th Aero Squadron's fallen heroes.

As unassumingly as he entered life, Jefferson Davis Vincent now rests. He rests alongside his brothers in arms, the ones who finished the task that he helped begin. His family was of too modest means to disturb his slumber and bring him home. He may desire to be nowhere else as a self-made hero of athleticism, academia, and patriotism: The archetype of what most Cornellians hope to be. He was the first great American-born hockey player, the greatest player in Cornell hockey history, and a true servant of the United States. He sleeps now with those who shared his great love of country and sacrificed equally in their efforts to defend her values.

Honored Evermore

On this Memorial Day, and on all others, remember the career of Jefferson Vincent and what it did to create our modern sense of Cornell University's identity. He was a student-athlete, morally guided scientist, scientifically literate public servant, and citizen-soldier. He was all the tensions that Cornell University was intended to be.

Jefferson Davis Vincent, a Cornellian in the purest sense, was as talented and brave as the greatest from his era. Cornellians, from current students to alumni, should think of him when they pass through the arch of the War Memorial on West Campus or catch a glimpse of its towers. When that particular time of year arrives, when the great adversary of our institution visits for a pitched contest on frozen terrain, perhaps leave a carnelian token at the panel of the War Memorial inscribed with Vincent's name as a sign of gratitude and remembrance.

"Their bodies sleep, but their souls live evermore," pontificated Reverend Newell D. Hillis during the memorial service of June 8, 1919. The body of the greatest college-hockey player rests thousands of miles from our sanctuary on East Hill. Now, there is some corner of a foreign field that is forever Cornell. Lest we allow ourselves to forget him and in so doing become less Cornellian.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed