The students of Cornell and Harvard have little love lost between them. They respect one another on some level, but that respect disappears upon direct comparison as they see only their distinction. From Cornell's perspective, Cornell is grade deflationary while Harvard is grade inflationary. Cornell is the "working class Ivy" "with a Big Ten heart" while Harvard is stilted. To borrow from Cornell's own marketing campaign in recent years, Cornell is elite while Harvard is elitist. Most Cornellians must realize that those distinctions between themselves and Harvard disappear to people outside of the Ivy League, if not just the Cornell-Harvard rivalry. However, these self-conceptions drive both Cornell and Harvard students to invest considerable energy and care in the tilts between the two programs.

One other level exists. Historically and institutionally, Cornell and Harvard are defined against one another since the founding of the former. Each borrows from the other but makes each adoption its own while assuming the superiority of its choices. The student populations of both universities dislikes one another. The Big Red and Crimsons players who represent each program harbor the same feelings toward each other as do their respective student populations. One can conclude that they are none too fond of each other. The greatest rivalries have yet another level. The historic leaders of great programs create, shape, and augment rivalries between their programs and their hated foes. The best rivalries in sports involve coaches who seize upon these rivalries to elevate their programs and in so doing make these competitions the stuff of legends. The Cornell-Harvard rivalry enjoys this oft-overlooked element as well.

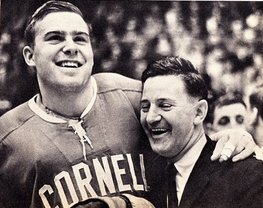

Cornell can claim proudly that it was led by the greatest coach in college hockey history. Ned Harkness led the Big Red from 1963 through 1970. He helped Cornell earn both of its national championships. He will be remembered forever in the annals of college hockey as a head coach who coached three teams for two different programs to national-championship success. Harkness is ranked 26th all-time in terms of absolute number of wins as a head coach. His greatest statistical accolade is that after 42 years since his coaching career ended, he holds still today the record for the best career winning percentage at 0.729. A record that is dwarfed only by Harkness' winning percentage at Cornell that is an astounding 0.854.

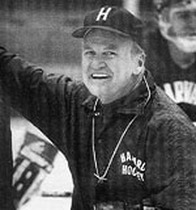

Harvard has a legend of its own to claim as its historical legendary coach. The legendary aspects of the story that belongs to Bill Cleary has less to do with his role as head coach of the Crimson and more to do with his contributions to the Harvard Line that helped Team USA claim the United States's first gold medal in men's ice hockey in the 1960 Olympics. Cleary coached for nearly 20 years at his alma mater of Harvard. Cleary ranks 31st all-time in terms of absolute number of wins among college hockey coaches. His career winning percentage as head coach is a modest 0.614. These statistics are coextensive with his career at his alma mater because he coached nowhere else.

Cleary helped Harvard claim two of its eight ECAC Championships and six of its 10 regular-season titles. Harkness helped Cornell earn four ECAC Championships and three regular-season titles of its current totals of 12 and eight respectively. Of the 84 titles that Cornell and Harvard have won collectively, the accolades that Cleary and Harkness accumulated account for 40% of that unequaled total.

Cleary took the position as coach of the freshman team at Harvard in 1968. He did not ascend to the position of head coach of Harvard hockey until after Harkness departed from East Hill in 1970. Cleary and Harkness never coached teams that confronted one another on the ice. Despite this fact, their roles in shaping the tone and central facets of the Cornell-Harvard rivalry cannot be understated. Cleary and Harkness added to the culture that surround the greatest rivalry in college hockey despite the separation of their tenures at their respective schools by one season.

One of the most modern dimensions of the Cornell-Harvard rivalry has its origins in the Harkness Era. Harkness began to recruit Canadian talent to East Hill upon his arrival at Cornell in 1963. That added a dimension to the rivalry that will be discussed later. The element that concerns us now is what was part of Harkness' recruiting pitch to potential student-athletes. He recruited student-athletes from Canada. Most of these recruits, as Harkness would describe later, were the sons of farmers in Canada who were expected to partake in their family's enterprises after receiving education.

The path to the NHL from college hockey was not trodden. In fact, it was one of Harkness' earliest recruits, Ken Dryden, who began to establish the viability and legitimacy of college hockey as a path to the NHL. Harkness would inform potential recruits of the opportunities to study agriculture at Cornell University, a subject area in which the University was required to offer instruction per its status as New York State's land-grant institution. Harkness' pitch afforded recruits the ability to play the sport that they loved while studying a topic that would help them in what was likely to be their life's profession.

Coaches at Harvard saw things quite differently. Cleary then was not the head coach at Harvard, so the first line of attack upon Cornell hockey and Cornell University began with his predecessor, Weiland. Harvard's line of attack went along the lines that the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Cornell offered an education unbefitting of an Ivy-League institution and that it provided Harkness with the ability to compete with athletes who were inferior academically to their counterparts at Harvard College. Notwithstanding the ignorance to most facts that one must enjoy to make this argument, the rivalry between Cornell and Harvard in men's ice hockey began to adopt an institutional tone.

The insult to the academic integrity of Cornell University as a proper Ivy-League institution and peer of Harvard has given rise to the modern era of taunts exchanged between Cornell and Harvard. The seeds of the modern chants of "safety school" and "grade inflation" no doubt have germs in the Harkness Era when Harvard criticized Cornell University and its student-athletes representative as inferior to its own. It is unsurprising that the Lynah Faithful would reciprocate a generation later with informing Harvard that it, not their beloved alma mater, was the safety school because it may be the hardest Ivy-League institution into which to gain admission, but it is the easiest from which to earn a degree with its lax grading policies and noted rampant grade inflation. The recognition of Cornell as one of the most grade deflationary institutions in the nation only has buoyed the modern generation of the Faithful to lob what many perceive and describe as a very stereotypical Ivy-League chant often. A chant that no matter how modern it may seem has its origins deep in the institutional memory of Cornell hockey from the Harkness Era.

Harvard may be able to claim that it revolutionized hockey with its creation of the line change (yes, this is a historical fact), however its most legendary coach has no such claim to fame. The same cannot be said of Cornell's Harkness. Harkness added a depth to the game of college hockey that had been not witnessed previously. He began the practice of putting a coach in the press box with a radio to take notes. Harkness would adjust his strategy mid-game to adapt to lessons from the observations of the coach with a better vantage point. This technique is blase now but ignited the ire of many of his coaching colleagues, not least of all those among the Crimson.

The taunting of "safety school" and "grade inflation" was not the only modern element that has its genesis in the Harkness Era born from his recruiting practices. The recruitment of Canadian players annoyed Harvard especially. Harvard forged its winning tradition upon American talent. It was one of the major hockey programs that lobbied to exclude Canadian players from competing in the ECAC or NCAA. Most viewed these attempts of Harvard during the Harkness Era and directly thereafter as a pointed affront to Cornell and its Canadian student-athletes. The stylistic choices of The Harvard Crimson make this assumption of Cornell all the more believable as it adopted "the Canadians" as a pejorative for Cornell in articles written about editions of the Cornell-Harvard rivalry.

Much like the Harvardian insults of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences in the Harkness Era, it did not take long for Cornell to reclaim and embrace the attempted slight. Cornellians, no matter their national origin, incorporated pride in their Canadian student-athletes into a unique tradition of the Lynah Faithful. Both the Canadian and American national anthems are played at Lynah Rink before each game. It is only befitting of a program that has many Canadian student-athletes that represent it today and one with a revered history that Canadian student-athletes played no small role in creating. The unique tradition of the Faithful however is that when Cornell plays at a venue or a neutral site that does not play the Canadian national anthem, which is not all too uncommon in the college hockey world, the Lynah Faithful celebrate the contributions of Canadian student-athletes past and present with singing the Canadian national anthem.

Harkness' many strategic and recruiting practices irritated the Crimson. It was those practices that allowed Harkness to build a winning hockey tradition of Cornell less than a decade after Cornell's first game in Lynah Rink. This winning tradition challenged and toppled the dominance that Harvard had enjoyed for several decades. It is unsurprising that Harvard began to call Harkness and by extension Cornell "the poison Ivy." Future Cornell fans and at least one future Cornell coach would have choicer words for Harvard's legendary head coach.

Several elements of the Cornell-Harvard rivalry are traced directly to the almost two-decade tenure of Bill Cleary. Cornell continued a grinding physical game that Harkness preferred even after his departure. Not much has changed in the 42 years since then in that aspect of Cornell hockey. Cleary preferred a more open-ice offense-based style of play. Cleary seized upon the renovation of Watson Rink (now Bright Hockey Center) and the fact that ice surfaces in rinks need not have a standard size. He chose to renovate the ice surface so that it would have a size of 204 feet x 87 feet. These dimensions are the current dimensions of Bright Hockey Center. Cleary rationalized that the elongated ice surface benefited his preferred style of open-ice play and disadvantaged those that played a more physical game along the boards. It is very unlikely that he did not have Cornell in mind when making this strategic change to the layout of Watson Rink.

Cleary contributed to the college hockey world in ways beyond the rivalry. As a Harvard man, his opposition to the participation of Canadian players in college hockey was predictable. This opposition changed and adapted, much like the institutional opposition of Harvard hockey, to different eras. Cleary opposed Canadian recruits playing college hockey after they had competed in any level of Canadian juniors whether it was a non-professionalized or professionalized junior league. He opposed the latter on the groups that he opposed vehemently student-athletes who are much older than their classmates by virtue of playing years in a junior league. He lost this battle as most Junior A leagues are feeders to even his program. His vision of prohibiting Canadian professionalized juniors has been maintained as there exists still an outright ban on the participation of Canadian major junior athletes form competing as student-athletes in college hockey.

Cleary is involved in several anecdotes that indicate how his tenure and his stewardship of Harvard hockey helped fan the flames of an already heated rivalry between Cornell and Harvard. His time as head coach is most readily identifiable with the time frame when the Cornell-Harvard rivalry took upon what many describe as its most characteristic element: the chicken and the fish toss. Cleary led the Crimson in 1973 when a Harvard fan threw a dead chicken on the ice. The chicken indicated that the insults that Harkness and his era of Cornell student-athletes endured about the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Cornell had gone nowhere. The Lynah Faithful responded with inundating the Crimson with fish to mock the primary industry of the host city of Harvard when it took the ice at Lynah Rink. Harvard fans, when they exist, will embrace the tradition of throwing dead fowl at the Big Red at Bright. As many know, the Lynah Faithful never miss a fish toss.

The other principal anecdotes about Cleary's time as head coach that involve the Cornell-Harvard rivalry involve directly and indirectly current Cornell head coach Mike Schafer. Once, he boldly left the Harvard bench to join fans in the stands at Lynah Rink. Cornell-Harvard-rivalry legend tells that Cleary did this to redirect the pressure off of his team at Lynah Rink to him. His team apparently was faring worse than usual in the particularly Crimson-hostile confines of Lynah. He did gain a great deal of attention as he sat near the sousaphones of the Cornell Pep Band. I am not sure if "Swanee River" was in the Pep Band's repertoire at that time, but the sousaphones of the Pep Band did give him an earful of whatever they were playing. Literally.

Cleary's reputation was notorious among Cornell players and the Faithful alike. It would be a grave understatement to say that he was disliked. One incident captures the level of dislike between Cleary and the Big Red vividly. Current Cornell head coach Schafer shot a puck at the Harvard bench direct at Cleary. It barely missed. What prompted it exactly is largely unknown, but the Lynah Faithful thought it was a proportional treatment for a coach that they viewed as loathsome.

The last anecdote involves Cleary's last official act as head coach of the Crimson. Cleary had announced before the 1989-90 season that he would retire when the season was complete. Seeding in the 1990 ECAC Tournament resulted in Cornell hosting Harvard in the quarterfinal round. Cornell swept the Crimson. Cleary was forced to end his career in front of a hostile crowd to a team that his players and he had ridiculed as competitively inferior in the days before the series. Instead of shaking hands with the Big Red after the series, Cleary ordered his team to leave the ice without congratulating the victorious Big Red. Cornell has not forgotten this openly hostile, disrespectful, and objectively unsportsmanlike act.

Schafer was an assistant coach for Cornell when Cleary ordered the Cantabs to behave in such an unsportsmanlike manner to insult Cornell. The ECAC named its regular-season title after Cleary in 2001. The Conference has named no formal accolades after Harkness. Cornell has won the regular-season title twice since it has born Cleary's name. The Lynah Faithful and Schafer have not and will not allow future players for the Big Red to forget Cleary's last official act as head coach of Cornell. This has led to Cornell's tradition of leaving the regular-season title trophy on the ice and refusing to touch it both times that Cornell has won it since 2001. Many of the Lynah Faithful will refuse to refer to the regular-season title trophy by its new name.

Harvard experienced a coaching change before the 2004-05. The Crimson were looking for a Schafer of its own. Harvard turned to Ted Donato to attempt to help guide Harvard back to national relevance. Donato has guided Harvard to two berths in the NCAA Tournament and one Whitelaw Cup in his eight-year tenure. These numbers in themselves do not indicate that Harvard has found the man to redirect its program toward the pinnacle of the sport. However, Donato has amassed a record of 10-11-1 in the Cornell-Harvard rivalry.

Schafer has gained near-legend status among the Faithful already. His contributions as a player and coach have endeared him to generations of loyal fans. The inclusion of Donato in a post about legendary coaches, when his status as such is still in flux, is to highlight how the nature of the Cornell-Harvard rivalry has changed since when Harkness and Cleary guided the greatest programs in the ECAC.

Schafer and Donato have a peculiar relationship. One need only watch their post-game handshake after Harvard handed Cornell the worst postseason defeat of either program in the 102-year history of the Cornell-Harvard rivalry. What were they both laughing about? First-season goals and a broken hockey stick in 1983 indicate that Schafer never takes games against the Crimson lightly. I think the interaction is very telling in the evolution of the rivalry to a different, more mature state.

Does it symbolize a loss of intensity? Not at all. It might illustrate an intensification. Examination of the rivalry through the lens of the coaches who oversaw it from its earlier stages under Harkness and Cleary to its current state under Schafer and Donato shows a change. The Cornell-Harvard rivalry has grown from outright vitriol and disrespect, from both sides, to a begrudging respect between two academic institutions that disagree historically on a fundamental basis and whose hockey programs are among the most storied in college hockey.

The current generation of the rivalry is one in which the programs value the rivalry in how it can make each program better. Cornell and Harvard, in academics and college hockey, want to prove that they are the best by measuring themselves by and defeating the best. The fortunes of Cornell and Harvard are tied mutually. Donato echoed these sentiments throughout his post-ECAC-Semifinal press conference. He spends a great deal of time praising Schafer and Cornell, and then wishes them luck sincerely in reaching the 2012 NCAA Tournament. The comments are in the below video in the introductions and at 3:54 specifically.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed